William Rosen at The Wall Street Journal hails these books about inventions.

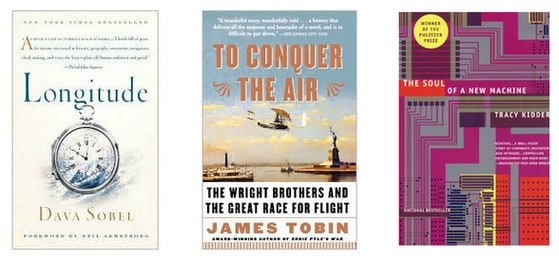

Longitude By Dava Sobel

The story of the first marine chronometer, invented by the self-taught British clockmaker John Harrison, had a remarkable number of dramatic elements. Thanks to the Longitude Act of 1714, the protagonist’s goal–a £20,000 prize for a method of determining longitude to within 30 nautical miles–could not have been clearer. Even more theatrically, Harrison was a legitimate “lone genius,” who spent 19 solitary years on a single version of a clock accurate enough to compare local noon at sea with noon back home. And, in the devious Nevil Maskelyne, astronomer royal and champion of a competing method of calculating longitude, the story had a perfect villain. To this raw material Dava Sobel added a sculptor’s sense for the physicality of things–for the self-lubricating gears that Harrison carved from close-grained wood–and enough poetic imagination to describe H-1, Harrison’s first chronometer, as “a model ship, escaped from its bottle, afloat on the sea of time.”

To Conquer the Air By James Tobin

The story of the onetime bicycle-shop owners from Dayton, Ohio (in 1900, America’s per capita patent leader), is simultaneously a brilliant panorama of early 20th-century America and an unforgettable portrait of Wilbur Wright. Both Wilbur and his brother Orville were exemplars of grace under pressure, showing high intelligence, modesty and determination without foolhardiness–all the while competing against everyone from Alexander Graham Bell to the motorcycle-racing champion Glenn Curtiss to be the first aloft. But Wilbur is clearly the star. His decision to master airborne stability and balance before power–to create the optimal wing and let the engine take care of itself–gives James Tobin’s tale an enormously satisfying structure, as well as an entirely apt metaphor for Wilbur Wright’s life.

The Soul of a New Machine By Tracy Kidder

The holy grail for Tom West and his team of computer engineers was a machine that was smaller and nimbler than a mainframe but still able to process 32 bits of information: a superminicomputer. Tracy Kidder chronicled their painstaking quest in one of the more improbable best sellers ever. (A book about writing software code?) But even now “The Soul of a New Machine” is capable of inducing in readers the same sleepless nights that the project demanded of the twentysomething geeks who designed and built the machine they dubbed the Eagle. “The real game is pinball,” West tells them. “You win one game, you get to play another; you build this machine, you get to build another.”

Photo by Walker & Company/Simon & Schuster/Back Bay Books.