- 1909 – Kinemacolor, the first successful color motion picture process, is first shown to the general public at the Palace Theatre in London.

- 1917 – The Original Dixieland Jass Band records the first jazz record, for the Victor Talking Machine Company in New York.

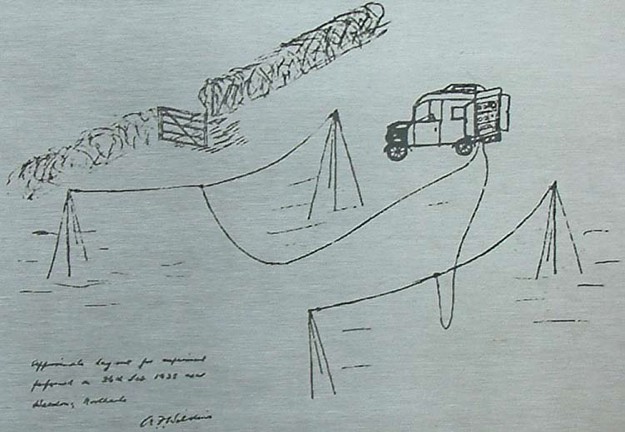

- 1935 – Robert Watson-Watt carries out a demonstration near Daventry which leads directly to the development of RADAR in the United Kingdom.

In 1934, the Air Ministry set up a committee chaired by Sir Henry Tizard to advance the state of the art of air defence in the UK. During World War I, the Germans had used Zeppelins as long-range bombers over London and other cities and defences had struggled to counter the threat. Since that time aircraft capabilities had improved considerably, and existing weapons were unlikely to have any effect on a raid.

The prospect of aerial bombardment of civilian areas was causing the government anxiety with heavy bombers able to approach from altitudes that anti-aircraft guns of the day were unable to reach. With the enemy airfields only 20 minutes away, the bombers would have dropped their bombs and be returning to base before the intercepting fighters could get to altitude. The only solution would be to have standing patrols of fighters in the air at all times, but with the limited cruising time of a fighter this would require a gigantic standing force. A plausible solution was urgently needed.

Nazi Germany was rumored to have a “death-ray” using radio waves that was capable of destroying towns, cities and people. In January 1935, H.E. Wimperis, Director of Scientific Research at the Air Ministry, asked Watson-Watt about the possibility of building their version of a death-ray, specifically to be used against aircraft. Watson-Watt quickly returned a calculation carried out by his assistant, Arnold Wilkins, showing that the device was impossible to construct, and fears of a Nazi version soon vanished. However he also mentioned in the same report: “Meanwhile attention is being turned to the still difficult, but less unpromising, problem of radio detection and numerical considerations on the method of detection by reflected radio waves will be submitted when required.”

For more, read the The pulse of radar: The autobiography of Sir Robert Watson-Watt.